Compute!

Music of the chapter: Computer Love - By Kraftwerk

Which came first? The chicken or the egg?

Imagine, for a moment, that a catastrophic event occurs, causing us to lose all the technology we once had. All that remains is ashes, and our situation is similar to humanity's early days millions of years ago. But there's one key difference: we still have the ability to read, and fortunately, many books are available that explain how our modern technology once worked. Now, here's an interesting question: How long would it take for us to reach the level of advancement we have today?

My prediction is that we would get back on track within a few decades. The only reason it might take longer than expected is that we would need tools to build other tools. For example, we can't just start building a modern CPU, even if we have the specifications and detailed design. First, we would need to rebuild the tools required to create complex electronic circuits. If we are starting from scratch, as we've assumed, we would also need to relearn how to find and extract the materials we need from the Earth, and then use those materials to make simpler tools. These simpler tools would then allow us to create more advanced ones. Here's the key point that makes all of our technological progress possible: technology can accelerate the creation of more technology!

Just like the chicken-and-egg paradox, I’ve often wondered how people built the very first compilers and assemblers. What language did they use to describe the first assembly languages? Did they have to write early assembler programs directly in 0s and 1s? After some research, I discovered that the answer is yes. In fact, as an example, the process of building a C compiler for the first time goes like this:

- First, you write a C compiler directly in machine code or assembly (or some other lower-level language).

- Next, you rewrite the same C compiler in C.

- Then, you compile the new C source code using the compiler written in assembly.

- At this point, you can completely discard the assembly implementation and treat the C compiler as if it were originally written in C.

See this beautiful loop? Technology sustains and reproduces itself, which essentially means technology is a form of life! The simpler computer language (in this case, machine-assembly) helped the C compiler emerge, but once the compiler was created, it could stand on its own. We no longer need the machine-assembly version, since there’s nothing stopping us from describing a C compiler in C itself! This phenomenon isn’t limited to software—just like a hammer can be used to build new hammers!

Now, let's return to our original question: Which came first, the chicken or the egg? If we look at the history of evolution, we can see that creatures millions of years ago didn’t reproduce by laying eggs. For example, basic living cells didn’t reproduce by laying eggs; they simply split in two. As living organisms evolved and became more complex, processes like egg-laying gradually emerged. The very first chicken-like animal that started laying eggs didn’t necessarily hatch from an egg. It could have been a mutation that introduced egg-laying behavior in a new generation, much like how a C compiler could come to life without depending on an assembly implementation.

When the dominos fall

If you ask someone deeply knowledgeable about computers how a computer works at the most fundamental level, they’ll probably start by talking about electronic switches, transistors, and logic gates. Well, I’m going to take a similar approach, but with a slight twist! While transistors are the basic building blocks of nearly all modern computers, the real magic behind what makes computers "do their thing" is something I like to call "Cause & Effect" chains.

Let’s begin by looking at some everyday examples of cause-and-effect scenarios. Here’s my list (feel free to add yours as you think of them):

- You press a key on your computer → A character appears on the screen → END

- You push the first domino → The next domino falls → The next domino falls → ...

- You ask someone to open the window → He opens the window → END

- You tell a rumor to your friend → He tells the rumor to his friend → ...

- You toggle the switch → The light bulb turns on → END

- A neuron fires in your brain → Another neuron gets excited and fires → ...

Now, let’s explore why some of these cause-and-effect chains keep going, setting off a series of events that lead to significant changes in their environment, while others stop after just a few steps. Why do some things trigger a cascade of actions, while others don’t?

There's an important pattern here: The long-lasting (i.e., interesting) effects emerge from cause-and-effect chains where the effects are of the same type as the causes. This means that these chains become particularly interesting when they can form cycles. For example, when a "mechanical" cause leads to another "mechanical" effect (like falling dominos), or when an "electrical" cause triggers another electrical effect (like in electronic circuits or the firing of neurons in your brain).

The most complex thing you can create with components that transform a single cause into a single effect is essentially no different from a chain of falling dominoes (or when rumors circulate within a company). While it’s still impressive and has its own interesting aspects, we don’t want to stop there. The real magic happens when you start transforming multiple causes into a single effect—especially when all the causes are of the same type. That’s when Cause & Effect chains truly come to life!

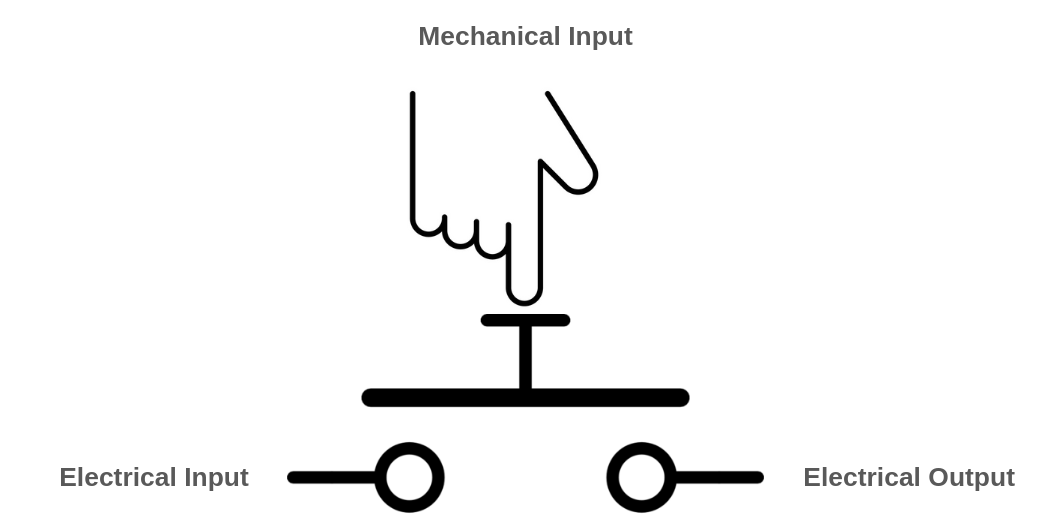

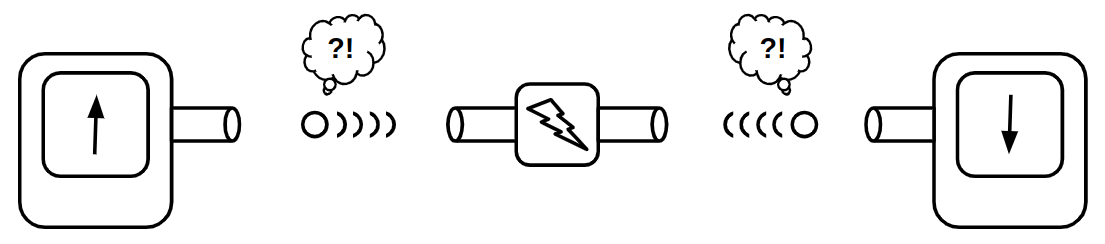

A simple example of a multi-input/single-output component is a switch. A switch controls the flow of an input to an output through a third, controlling input. Light switches, push buttons, and faucets (which control the flow of water through a pipe) are all examples of switches. However, in these cases, the type of the controlling input is different from the other inputs and outputs. For instance, the controlling input of a push button is mechanical, while the others are electrical. You still need a finger to push the button, and the output of the push button cannot be used as the mechanical input of another button. As a result, you can't build domino-like structures or long-lasting cause-and-effect chains using faucets or push buttons in the same way you would with purely similar types of inputs and outputs!

{ width=350px }

{ width=350px }

A push-button becomes more interesting when its controlling input is electrical rather than mechanical. In this case, all of its inputs and outputs are of the same type, allowing you to connect the output of one push-button to the controlling input of another.

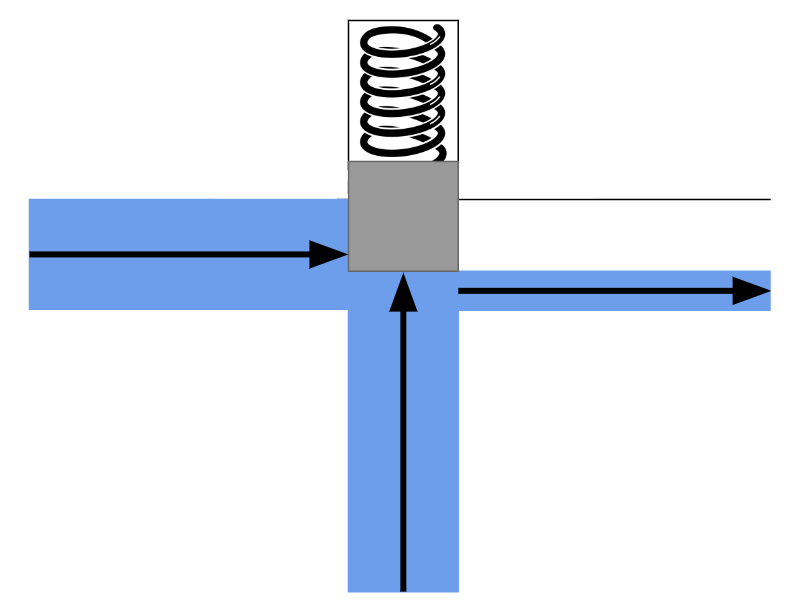

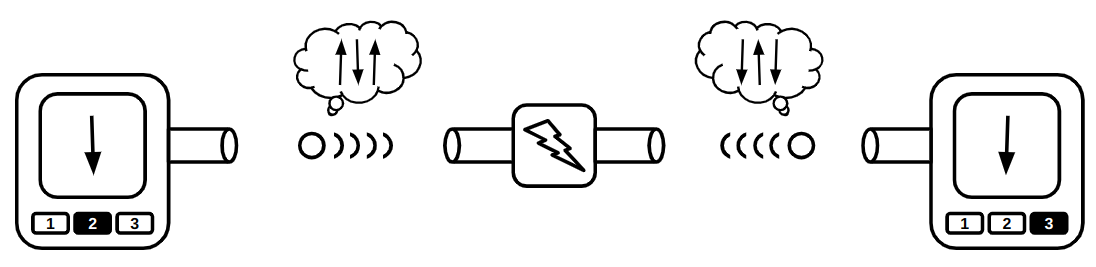

Similarly, in the faucet example, you could design a special kind of faucet that opens with the force of water, rather than requiring a person to open it manually with their hands. In the picture below, when no water is present in the controlling pipe (the pipe in the middle), the spring will push the block down, preventing water from flowing from the left pipe to the right pipe. However, when water enters the controlling pipe, its pressure will push the block up, creating space for the water to flow from the left pipe to the right pipe.

{ width=350px }

{ width=350px }

The controlling input doesn't have to sharply switch the flow between no-flow and maximum-flow. Instead, the controller can adjust the flow to any level, depending on how much the controlling input is pushed. Additionally, the controlling input doesn't need to be as large or powerful as the other inputs/outputs. It could be a thinner pipe that requires only a small force of water to fully open the valve. This means you can control a large and powerful water flow using a much smaller input and less force.

There’s also a well-known name for these unique switches: transistors. Now you can understand what "transistor" literally means—it’s something that can "transfer" or adjust "resistance" on demand, much like how we can control the resistance of the water flow in a larger pipe using a third input.

The most obvious use case for a transistor is signal amplification. Let’s explore this with an example: imagine a small pipe through which water flows in a sinusoidal pattern. Initially, there is no water, then the flow gradually increases to a certain level, and finally, it slowly decreases back to zero (a pattern similar to what you might see in a water show!). Now, we connect this pipe to the controlling input of the water transistor we designed earlier. Can you guess what comes out from the output of this transistor? Yes, the output is also a sinusoidal flow of water. The difference is that it’s much more powerful than the small pipe. We’ve just transferred the sinusoidal pattern from a small water flow to a much more powerful one! Can you imagine how important this is? This concept forms the core of how devices like electric guitars and sound amplifiers work!

That’s not the only use case for transistors, though. Because the cause-and-effect types of the inputs and outputs are the same, we can chain them together—and that’s all we need to start building machines that can compute things (we’ll explore the details soon!). These inputs don’t necessarily have to be electrical; they can be mechanical as well. Yes, we can build computers that operate using the force of water!

A typical transistor in the real world is conceptually the same as our imaginary faucet described above. Substitute water with electrons, and you have an accurate analogy for a transistor. Transistors, the building blocks of modern computers, allow you to control the flow of electrons in a wire using a third source of electrons!

Understanding how modern electron-based transistors work involves a fair bit of physics and chemistry. But if you insist, here’s a very simple (and admittedly silly) example of a push-button with an electrical controller: Imagine a person holding a wire in their hand. This person presses the push-button whenever they feel electricity in their hand (as long as the electricity isn’t strong enough to harm them). Together, the person and the push-button form something akin to a transistor, because now the types of all inputs and outputs in the system are the same.

It might sound like the strangest idea in the world, but if you had enough of these "transistors" connected together, you could theoretically build a computer capable of connecting to the internet and rendering webpages!

Why did people choose electrons to flow in the veins of our computers instead of something like water? There are several reasons:

- Electrons are extremely small.

- Electrical effects propagate extremely fast!

Thanks to these properties, we can create complex and dense cause-and-effect chains that produce amazing behaviors while using very little space, like in your smartphone!

Taming the electrons

In the previous section, we explored what a transistor is. Now it’s time to see what we can do with it! To quickly experiment with transistors, we’ll simulate imaginary transistors on a computer and arrange them in the right order to perform fancy computations for us.

Our ultimate goal is to construct a fully functional computer using a collection of three-way switches. If you have prior experience designing hardware, you're likely familiar with software tools that allow you to describe hardware using a Hardware Description Language (HDL). These tools can generate transistor-level circuits from your designs and even simulate them for you. However, since this book focuses on the underlying concepts rather than real-world, production-ready implementations, we will skip the complexity of learning an HDL. Instead, we'll use the Python programming language to emulate these concepts as we progress. This approach will not only deepen our understanding of the transistor-level implementation of something as intricate as a computer but also shed light on how HDL languages transform high-level circuit descriptions into collections of transistors.

So let's begin and start building our own circuit simulator!

Everything is relative

The very first term you encounter when exploring electricity is "voltage," so it’s essential to grasp its meaning before studying how transistors behave under different voltages. Formally, voltage is the potential energy difference between two points in a circuit. To understand this concept, let’s set aside electricity for a moment and think about heights.

Imagine lifting a heavy object from the ground. The higher you lift it, the more energy you expend (and the more tired you feel, right? That energy needs to be replenished, like by eating food!). According to the law of conservation of energy, energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed or transferred. So where does the energy you used to lift the object go?

Now, release the object and let it fall. It hits the ground with a bang, possibly breaking the ground—or itself. The higher the object was lifted, the greater the damage it causes. Clearly, energy is needed to create those noises and damages. But where did that energy come from?

You’ve guessed it! When you lifted the object, you transferred energy to it. When you let it fall, that stored energy was released. Physicists call this stored energy "potential energy." A raised object has the potential to do work (work is the result of energy being consumed), which is why it’s called potential energy!

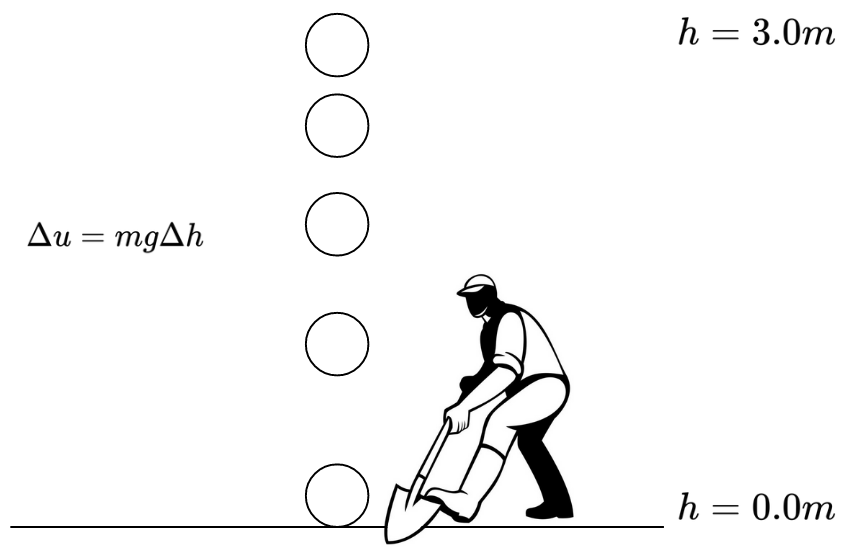

If you remember high school physics, you’ll know that the potential energy of an object can be calculated using the formula: \(U=mgh\), where \(m\) is the mass of the object, \(h\) is its height above the ground, and \(g\) is the Earth's gravitational constant (approximately \(9.807 m/s^2\)).

According to this formula, when the object is on the ground (\(h=0\)), the potential energy is also \(U=0\). But here’s an important question: does that mean an object lying on the ground has no potential energy?

Actually, it does have potential energy! Imagine taking a shovel and digging a hole under the object. The object would fall into the hole, demonstrating that it still had the capacity to do work due to gravity.

The key point is this: the equation \(U=mgh\) represents the potential energy difference relative to a chosen reference point (in this case, the ground), not the absolute potential energy of the object. A more precise way to express this idea would be: \(\varDelta{u}=mg\varDelta{h}\).

This equation shows that the potential energy difference between two points \(A\) and \(B\) depends on \(mg\), the gravitational force, and \(\varDelta{h}\), the difference in height between the two points.

In essence, potential energy is relative!

{ width=350px }

{ width=350px }

The reason it takes energy to lift an object is rooted in the fact that massive bodies attract each other, as described by the universal law of gravitation: \(F=G\frac{m_1m_2}{r^2}\).

Similarly, a comparable law exists in the microscopic world, where electrons attract protons, and like charges repel each other. This interaction is governed by Coulomb's law: \(F=k_e\frac{q_1q_2}{r^2}\)

As a result, we also have the concept of "potential energy" in the electromagnetic world. It takes energy to separate two electric charges of opposite types (positive and negative), as you're working against the attractive electric force. When you pull them apart and then release them, they will move back toward each other, releasing the stored potential energy.

That's essentially how batteries work. They create potential differences by moving electrons to higher "heights" of potential energy. When you connect a wire from the negative pole of the battery to the positive pole, the electrons "fall" through the wire, releasing energy in the process.

When we talk about "voltage," we are referring to the difference in height or potential energy between two points. While we might not know the absolute potential energy of points A and B, we can definitely measure and understand the difference in potential (voltage) between them!

Pipes of electrons

We discussed that transistors are essentially three-way switches that control the flow between two input/output paths using a third input. When building a transistor circuit simulator—whether simulating the flow of water or electrons—it makes sense to begin by simulating the "pipes," the elements through which electrons will flow. In electrical circuits, these "pipes" are commonly referred to as wires.

Wires are likely to be the most fundamental and essential components of our circuit simulation software. As their name suggests, wires are conductors of electricity, typically made of metal, that allow different components to connect and communicate via the flow of electricity. We can think of wires as containers that hold electrons at specific voltage levels. If two wires with different voltage levels are connected, electrons will flow from the wire with higher voltage to the one with lower voltage.

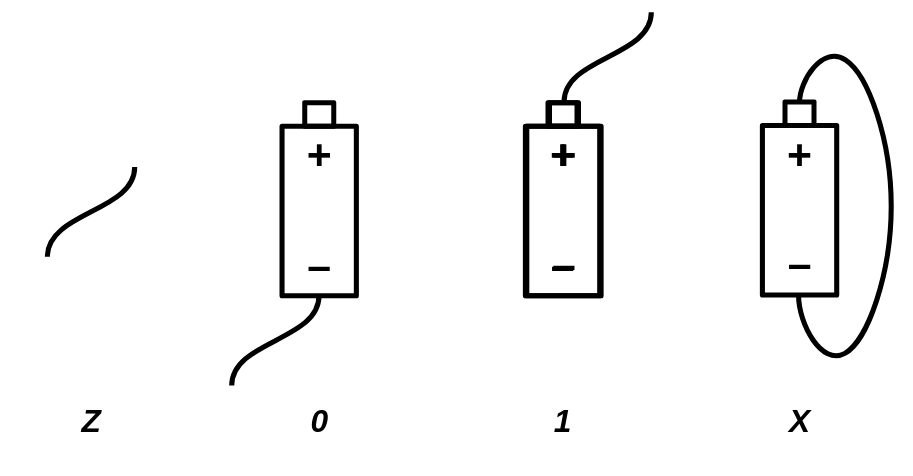

In digital circuits, transistors and other electronic components operate using two specific voltage levels: "zero" (commonly referred to as ground) and "one." It’s important to emphasize that the terms "zero" and "one" do not correspond to fixed or absolute values. Instead, "zero" acts as a reference point, while "one" represents a voltage level that is higher relative to "zero."

At first glance, it might seem that we could model a wire using a single boolean value: false to represent zero and true to represent one. However, this approach fails to account for all the possible scenarios that can arise in a circuit simulator.

For example, consider a wire in your simulator that isn’t connected to either the positive or negative pole of a battery. Would it even have a voltage level? Clearly, it would be neither 0 nor 1. Now imagine a wire that connects a high-voltage (1) wire to a low-voltage (0) wire. What would the voltage of this intermediary wire be? Electrons would start flowing from the higher-voltage wire to the lower-voltage wire, and as a result, the voltage of the intermediary wire would settle somewhere between 0 and 1.

In a digital circuit, connecting a 0 wire to a 1 wire is not always a good idea and could indicate a mistake in your circuit design, potentially causing a short circuit. Therefore, it is useful to consider a value for a wire that is either mistakenly or intentionally left unconnected (Free state) or connected to both 0 and 1 voltage sources simultaneously (Short-circuit/Unknown state).

Based on this explanation, a wire can be in four different states:

Zstate - The wire is free and not connected to anything.0state - The wire is connected to a ground voltage source and has 0 voltage.1state - The wire is connected to a 5.0V voltage source.Xstate - The wire's voltage cannot be determined because it is connected to both a 5.0V and 0.0V voltage source simultaneously.

Initially, a wire that is not connected to anything is in the Z state. When you connect it to a gate or wire that has a state of 1, the wire's state will also become 1. A wire can connect to multiple gates or wires at the same time. For example, if a wire already in the 1 state is connected to another source of 1, it will remain 1. However, the wire will enter the X state if it is connected to a wire or gate with a conflicting value. For instance, if the wire is connected to both 0 and 1 voltage sources simultaneously, its state will be X. Similarly, connecting any wire to an X voltage source will also result in the wire taking on the X state.

We can summarize all the possible scenarios in a custom table that defines the arithmetic of wire states:

| A | B | A + B |

|---|---|---|

| Z | Z | Z |

| 0 | Z | 0 |

| 1 | Z | 1 |

| X | Z | X |

| Z | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | X |

| X | 0 | X |

| Z | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | X |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| X | 1 | X |

| Z | X | X |

| 0 | X | X |

| 1 | X | X |

| X | X | X |

A wildcard version of this table would look like this:

| A | B | A + B |

|---|---|---|

| Z | x | x |

| x | Z | x |

| X | x | X |

| x | X | X |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | X |

| 1 | 0 | X |

Based on the explanation, we can model a wire as a Python class:

FREE = "Z"

UNK = "X"

ZERO = 0

ONE = 1

class Wire:

def __init__(self):

self._drivers = {}

self._assume = FREE

def assume(self, val):

self._assume = val

def get(self):

curr = FREE

for b in self._drivers.values():

if b == UNK:

return UNK

elif b != FREE:

if curr == FREE:

curr = b

elif b != curr:

return UNK

return curr if curr != FREE else self._assume

def put(self, driver, value):

is_changed = self._drivers.get(driver) != value

self._drivers[driver] = value

return is_changed

The code above models a wire as a Python class. By definition, a wire that is not connected to anything remains in the Z state. Using the put function, a driver (such as a battery or a gate) can apply a voltage to the wire. The final voltage of the wire is determined by iterating over all the voltages applied to it.

We store the voltage values applied to the wire in a dictionary to ensure that a single driver cannot apply two different values to the same wire.

The put function also checks whether there has been a change in the values applied to the wire. This will later help our simulator determine if the circuit has reached a stable state, where the values of all wires remain fixed.

In some cases—particularly in circuits containing feedback loops and recursion—it is necessary to assume that a wire already has a value in order to converge on a solution. For this purpose, we have designed the assume() function, which allows us to assign an assumed value to a wire if no gates have driven a value into it. If you don’t yet fully understand what the assume() function does, don’t worry—we’ll explore its usage in the next sections.

Magical switches

Now that we've successfully modeled wires, it's time to implement the second most important component of our simulator: the transistor.

Transistors are electrically controlled switches with three pins: base, emitter, and collector. These pins connect to other circuit elements through wires. The base pin acts as the switch’s controller—when there is a high potential difference between the base and collector pins, the emitter connects to the collector. Otherwise, the emitter remains unconnected, behaving like a floating wire in the Z state.

This key behavior means that turning off the transistor does not set the emitter to 0 but instead leaves it in the Z state.

We can also describe the wire arithmetic of a transistor using the following table:

| B | E | C |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | Z |

| 0 | 1 | Z |

| 1 | 0 | 0 (Strong) |

| 1 | 1 | 1 (Weak) |

The transistor we have been discussing so far is a Type-N transistor. The Type-N transistor turns on when the base wire is driven with a 1. There is also another type of transistor, known as Type-P, which turns on when the base wire is driven with a 0. The truth table for a Type-P transistor looks like this:

| B | E | C |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 (Weak) |

| 0 | 1 | 1 (Strong) |

| 1 | 0 | Z |

| 1 | 1 | Z |

Assuming we define a voltage of 5.0V as 1 and a voltage of 0.0V as 0, a wire is driven with a strong 0 when its voltage is very close to 0 (e.g., 0.2V), and a strong 1 when its voltage is close to 5 (e.g., 4.8V). The truth is, the transistors we build in the real world aren't ideal, so they won't always provide strong signals. A signal is considered weak when it's far from 0.0V or 5.0V. For example, a voltage of 4.0V could be considered a weak 1, and a voltage of 1.0V would be considered a weak 0, whereas 4.7V could be considered a strong 1 and 0.3V a strong 0. Type-P transistors, when built in the real world, are very good at producing strong 0 signals, but their 1 signals tend to be weak. On the other hand, Type-N transistors produce strong 1 signals, but their 0 signals are weak. By using both types of transistors together, we can build logic gates that provide strong outputs in all cases.

The Transistor

In our digital circuit simulator, we’ll have two different types of components: primitive components and components that are made of primitives. We’ll define components as primitives when they can’t be described as a group of smaller primitives.

For example, we can simulate Type-N and Type-P transistors as primitive components, since everything else can be constructed by combining Type-N and Type-P transistors together.

class NTransistor:

def __init__(self, in_base, in_collector, out_emitter):

self.in_base = in_base

self.in_collector = in_collector

self.out_emitter = out_emitter

def update(self):

b = self.in_base.get()

if b == ONE:

return self.out_emitter.put(self, self.in_collector.get())

elif b == ZERO:

return self.out_emitter.put(self, FREE)

elif b == UNK:

return self.out_emitter.put(self, UNK)

else:

return True # Trigger re-update

class PTransistor:

def __init__(self, in_base, in_collector, out_emitter):

self.in_base = in_base

self.in_collector = in_collector

self.out_emitter = out_emitter

def update(self):

b = self.in_base.get()

if b == ZERO:

return self.out_emitter.put(self, self.in_collector.get())

elif b == ONE:

return self.out_emitter.put(self, FREE)

elif b == UNK:

return self.out_emitter.put(self, UNK)

else:

return True # Trigger re-update

Our primitive components are classes with an update() function. The update() function is called whenever we want to calculate the output of the primitive based on its inputs. As a convention, we will prefix the input and output wires of our components with in_ and out_, respectively.

The update() function of our primitive components will also return a boolean value, which indicates whether the element needs to be updated again. Sometimes, the inputs of a component might not be ready when the update() function is called. For example, in the case of transistors, if the base wire is in the Z state, we assume there is another transistor that needs to be updated before the current transistor can calculate its output. By returning this boolean value, we inform our circuit emulator that the transistor is not "finalized" yet, and the update() function needs to be called again before determining that all component outputs have been correctly calculated and the circuit is stabilized.

Additionally, remember that the put() function of the Wire class also returns a boolean value. This value indicates whether the driver of that wire has placed a new value on the wire. A new value on a wire means there has been a change in the circuit, and the entire circuit needs to be updated again.

The Circuit

Now, it would be useful to have a data structure for keeping track of the wires and transistors allocated in a circuit. We will call this class Circuit. It will provide methods for creating wires and adding transistors. The Circuit class is responsible for calling the update() function of the primitive components and will allow you to calculate the values of all the wires in the network.

class Circuit:

def __init__(self):

self._wires = []

self._comps = []

self._zero = self.new_wire()

self._zero.put(self, ZERO)

self._one = self.new_wire()

self._one.put(self, ONE)

def one(self):

return self._one

def zero(self):

return self._zero

def new_wire(self):

w = Wire()

self._wires.append(w)

return w

def add_component(self, comp):

self._comps.append(comp)

def num_components(self):

return len(self._comps)

def update(self):

has_changes = False

for t in self._comps:

has_changes = has_changes | t.update()

return has_changes

def stabilize(self):

while self.update():

pass

The update() method of the Circuit class calculates the values of the wires by iterating through the transistors and calling their update method. In circuits with feedback loops, a single iteration of updates may not be sufficient, and multiple iterations may be needed before the circuit reaches a stable state. To address this, we introduce an additional method specifically designed for this purpose: stabilize(). This method repeatedly performs updates until no changes are observed in the wire values, meaning the circuit has stabilized.

Our Circuit class also provides global zero() and one() wires, which can be used by components requiring fixed 0 and 1 signals. These wires function like battery poles in our circuits.

Electronic components can be defined as functions that take a circuit as input and add wires and transistors to it. Let’s explore the implementation details of some of them!

Life in a non-ideal world

Digital circuits are essentially logical expressions that are automatically evaluated by the flow of electrons through what we refer to as gates. Logical expressions are defined using zeros and ones, but as we have seen, wires in an electronic circuit are not always guaranteed to be either 0 or 1. Therefore, we must redefine our gates and determine their output in cases where the inputs are faulty.

Consider a NOT gate as an example. In an ideal world, its truth table would be as follows:

| A | NOT A |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 |

However, the real world is not ideal, and wires connected to electronic logic gates can have unexpected voltages. Since a wire in our emulation can have four different states, our logic gates must be able to handle all four. The following is the definition of a NOT gate using our wire arithmetic. If the input to the NOT gate is Z or X, the output will be the faulty state X.

| A | NOT A |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 |

| Z | X |

| X | X |

There are two ways to simulate gates in our software. We can either implement them using plain Python code as primitive components, similar to transistors, or we can construct them as a circuit of transistors. The following is an example of a NOT gate implemented using the first approach:

class Not:

def __init__(self, wire_in, wire_out):

self.wire_in = wire_in

self.wire_out = wire_out

def update(self):

v = self.wire_in.get()

if v == FREE:

self.wire_out.put(self, UNK)

elif v == UNK:

self.wire_out.put(self, UNK)

elif v == ZERO:

self.wire_out.put(self, ONE)

elif v == ONE:

self.wire_out.put(self, ZERO)

We can also test out implementation:

if __name__ == '__main__':

inp = Wire.zero()

out = Wire()

gate = Not(inp, out)

gate.update()

print(out.get())

The NOT gate modeled as a primitive component is accurate and functions as expected. However, we know that a NOT gate is actually built from transistors, and it might be more interesting to model it using a pair of transistors rather than cheating by emulating its high-level behavior with Python code.

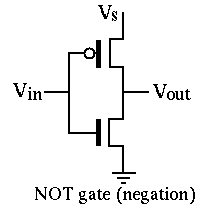

The following is an example of a NOT gate constructed using a P-type and an N-type transistor:

def Not(circuit, inp, out):

circuit.add_component(PTransistor(inp, circuit.one(), out))

circuit.add_component(NTransistor(inp, circuit.zero(), out))

As you know, an N-type transistor connects its source pin to its drain pin when the voltage on its gate is higher than the voltage on its drain. So, when the inp wire is driven with 1, the output gets connected to the circuit.zero() wire, causing out to hold a 0 signal. Notice that the P-type transistor is off when inp is 1, so the circuit.one() wire will not get connected to the output pin. If that were the case, we would get a short circuit, causing the out signal to become a faulty (X)`.

Likewise, when inp is 0, the P-type transistor turns on and connects the output to circuit.one(), while the N-type transistor turns off, leaving the output unconnected to the ground.

NOT gates are probably the simplest components you can build using the current primitive elements provided by our simulator. Now that we’re familiar with transistors, it’s time to expand our component set and build some of the most fundamental logic gates. In addition to NOT gates, you’ve likely heard of AND and OR gates, which are a bit more complex—mainly because they take more than one input. Here’s their definition:

AND gate: outputs 0 when at least one of the inputs is 0, and gets 1 when all of the inputs are 1. Otherwise the output is faulty (X).

| A | B | A AND B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | * | 0 |

| * | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| X |

OR gate: outputs 1 when at least one of the inputs is 1, and gets 0 only when all of the inputs are 0. Otherwise the output is unknown (X).

| A | B | A OR B |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | * | 1 |

| * | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| X |

Mother of the gates

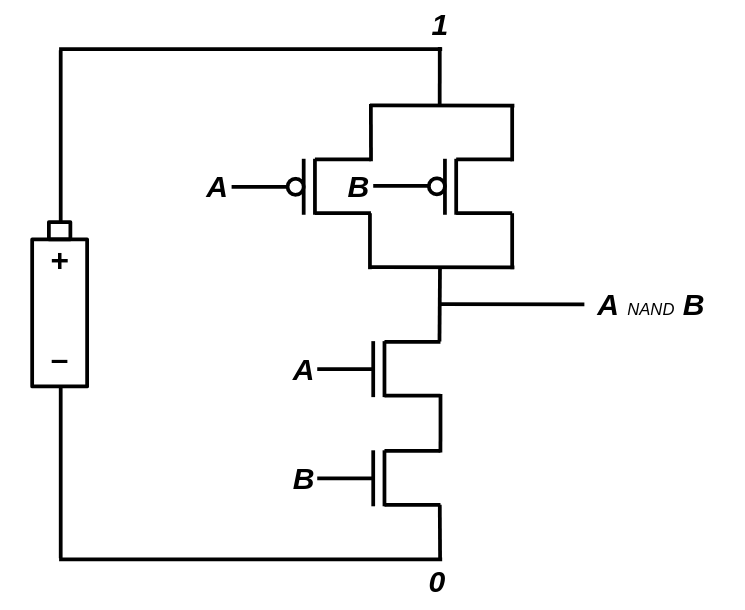

A NAND gate is a logic gate that outputs 0 if and only if both of its inputs are 1. It is essentially an AND gate with its output inverted. It can be proven that all the basic logic gates (AND, OR, NOT) can be built using different combinations of this single gate:

- \(NOT(x) = NAND(x, x)\)

- \(AND(x, y) = NOT(NAND(x, y)) = NAND(NAND(x, y), NAND(x, y))\)

- \(OR(x, y) = NAND(NOT(x), NOT(y)) = NAND(NAND(x, x), NAND(y, y))\)

It is the "mother gate" of all logic circuits. Although building everything with NAND gates would be very inefficient in practice, for the sake of simplicity, we'll stick to NAND gates and try to construct other gates by connecting them together.

It turns out that we can build NAND gates with strong and accurate output signals using 4 transistors (2 Type-N and 2 Type-P). Let's prototype a NAND gate using our simulated N/P transistors!

def Nand(circuit, in_a, in_b, out):

inter = circuit.new_wire()

circuit.add_component(PTransistor(in_a, circuit.one(), out))

circuit.add_component(PTransistor(in_b, circuit.one(), out))

circuit.add_component(NTransistor(in_a, circuit.zero(), inter))

circuit.add_component(NTransistor(in_b, inter, out))

Now, other primitive gates can be defined as combinations of NAND gates. Take the NOT gate as an example. Here is a third way we can implement a NOT gate (So far, we have implemented a NOT gate in two ways: 1. Describing its behavior through plain Python code, and 2. By connecting a pair of Type-N and Type-P transistors):

def Not(circuit, inp, out):

Nand(circuit, inp, inp, out)

Go ahead and implement the other primitive gates using the NAND gate we just defined. After that, we can start creating useful circuits from these gates!

def And(circuit, in_a, in_b, out):

not_out = circuit.new_wire()

Nand(circuit, in_a, in_b, not_out)

Not(circuit, not_out, out)

def Or(circuit, in_a, in_b, out):

not_out = circuit.new_wire()

Nor(circuit, in_a, in_b, not_out)

Not(circuit, not_out, out)

def Nor(circuit, in_a, in_b, out):

inter = circuit.new_wire()

circuit.add_component(PTransistor(in_a, circuit.one(), inter))

circuit.add_component(PTransistor(in_b, inter, out))

circuit.add_component(NTransistor(in_a, circuit.zero(), out))

circuit.add_component(NTransistor(in_b, circuit.zero(), out))

An XOR gate is another incredibly useful gate that comes in handy when building circuits that can perform numerical additions. The XOR gate outputs 1 only when the inputs are unequal, and outputs 0 when they are equal. XOR gates can be built from AND, OR, and NOT gates: \(Xor(x,y) = Or(And(x, Not(y)), And(Not(x), y))\). However, since XOR gates will be used frequently in our future circuits, it makes more sense to provide a transistor-level implementation for them, as this will require fewer transistors!

def Xor(circuit, in_a, in_b, out):

a_not = circuit.new_wire()

b_not = circuit.new_wire()

Not(circuit, in_a, a_not)

Not(circuit, in_b, b_not)

inter1 = circuit.new_wire()

circuit.add_component(PTransistor(b_not, circuit.one(), inter1))

circuit.add_component(PTransistor(in_a, inter1, out))

inter2 = circuit.new_wire()

circuit.add_component(PTransistor(in_b, circuit.one(), inter2))

circuit.add_component(PTransistor(a_not, inter2, out))

inter3 = circuit.new_wire()

circuit.add_component(NTransistor(in_b, circuit.zero(), inter3))

circuit.add_component(NTransistor(in_a, inter3, out))

inter4 = circuit.new_wire()

circuit.add_component(NTransistor(b_not, circuit.zero(), inter4))

circuit.add_component(NTransistor(a_not, inter4, out))

Sometimes, we simply need to connect two different wires. Instead of creating a new primitive component for that purpose, we can use two consecutive NOT gates. This will act like a simple jumper! We'll call this gate a Forward gate:

def Forward(circuit, inp, out):

tmp = circuit.new_wire()

Not(circuit, inp, tmp)

Not(circuit, tmp, out)

Hello World circuit!

The simplest digital circuit we might consider a "computer" is one that can perform basic arithmetic, like adding two numbers together. In digital circuits, information is represented using binary signals—0s and 1s. So, when we talk about adding numbers in a digital circuit, we're working with binary numbers.

To start with, let's focus on a very basic example: a circuit that can add two one-bit binary numbers. A one-bit number can only be either a 0 or a 1, so adding them together can yield one of three possible results: 0 + 0 = 0, 0 + 1 = 1, and 1 + 1 = 10 (which is 2 in decimal). Notice that the result of adding two one-bit numbers is always a two-bit number, because 1 + 1 produces a carry, which means we need two bits to store the result.

To design such a circuit, one of the most effective approaches is to start by figuring out what the output should be for each possible combination of inputs. Since there are two inputs (each one-bit numbers), there are four possible input combinations: 00, 01, 10, and 11. For each of these combinations, we can determine what the output should be. Since the result is always a two-bit number, we can break the circuit into two smaller subcircuits: one that calculates the sum bit (the least significant bit) and one that calculates the carry bit (the more significant bit). Each subcircuit works independently to compute its corresponding part of the result.

In this way, we approach building the circuit step by step, using logic gates to implement the required operations for each input combination.

| A | B | First digit | Second digit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

The relation of the second digit with A and B is very familiar; it's essentially an AND gate! Try to figure out how the first digit can be calculated by combining primitive gates. (Hint: It outputs 1 only when A is 0 AND B is 1, or A is 1 AND B is 0.)

Answer: It's an XOR gate! (\(Xor(x, y) = Or(And(x, Not(y)), And(Not(x), y))\)), and here is the Python code for the entire thing:

def HalfAdder(circuit, in_a, in_b, out_sum, out_carry):

Xor(circuit, in_a, in_b, out_sum)

And(circuit, in_a, in_b, out_carry)

What we have just built is known as a half-adder. With a half-adder, you can add 1-bit numbers together. You might think that we can build multi-bit adders by stacking multiple half-adders in a row, but that's not entirely correct. Recall that the addition algorithm we learned in primary school also applies to binary numbers. Imagine we want to add the binary numbers 1011001 (89) and 111101 (61) together. Here’s how it works:

1111 1

1011001

+ 111101

-----------

10010110

By examining the algorithm, we can see that for each digit, the addition involves three bits (not just two). In addition to the original bits, there is also a third carry bit from the previous addition that must be considered. Therefore, to design a multi-bit adder, we need a circuit that can add three one-bit numbers together. Such a circuit is known as a full-adder, and the third number is often referred to as the carry bit. Here’s the truth table for a three-bit adder:

| A | B | C | D0 | D1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Building a full-adder is not that challenging. You can use two half-adders to compute the sum bit and then take the OR of the carry outputs to obtain the final carry bit.

def FullAdder(circuit, in_a, in_b, in_carry, out_sum, out_carry):

sum_ab = circuit.new_wire()

carry1 = circuit.new_wire()

carry2 = circuit.new_wire()

HalfAdder(circuit, in_a, in_b, sum_ab, carry1)

HalfAdder(circuit, sum_ab, in_carry, out_sum, carry2)

Or(circuit, carry1, carry2, out_carry)

Once we have a full-adder ready, we can proceed with building multi-bit adders. For example, to create an 8-bit adder, we need to connect eight full-adders in a row. The carry output of each adder serves as the carry input for the next, mimicking the addition algorithm we discussed earlier.

def Adder8(circuit, in_a, in_b, in_carry, out_sum, out_carry):

carries = [in_carry] + [circuit.new_wire() for _ in range(7)] + [out_carry]

for i in range(8):

FullAdder(

circuit,

in_a[i],

in_b[i],

carries[i],

out_sum[i],

carries[i + 1],

)

Congratulations! We just added two 8-bit numbers using nothing but bare transistors. Before continuing our journey toward more complex circuits, let's ensure that our simulated model of the 8-bit adder is functioning correctly. If the 8-bit adder works properly, there is a high chance that the other gates are also functioning as expected.

def num_to_wires(circuit, num):

wires = []

for i in range(8):

bit = (num >> i) & 1

wires.append(circuit.one() if bit else circuit.zero())

return wires

def wires_to_num(wires):

out = 0

for i, w in enumerate(wires):

if w.get() == ONE:

out += 2**i

return out

if __name__ == "__main__":

for x in range(256):

for y in range(256):

circuit = Circuit()

wires_x = num_to_wires(circuit, x)

wires_y = num_to_wires(circuit, y)

wires_out = [Wire() for _ in range(8)]

Adder8(circuit, wires_x, wires_y, circuit.zero(), wires_out, circuit.zero())

circuit.update()

out = wires_to_num(wires_out)

if out != (x + y) % 256:

print("Adder is not working!")

Here, we are checking if the outputs are correct for all possible inputs. We have defined two auxiliary functions, num_to_wires and wires_to_num, to convert numbers into a set of wires that can connect to an electronic circuit, and vice versa.

When addition is subtraction

So far, we have been able to implement the addition operation by combining N and P transistors. Our adder is limited to 8 bits, meaning that the input and output values are all in the range \([0,255]\). If you try to add two numbers whose sum exceeds 255, you will still get a result in the range \([0,255]\). This happens because a number larger than 255 cannot be represented by 8 bits, and an overflow occurs. Upon closer inspection, you’ll notice that what we have designed isn’t the typical addition operation we are used to in elementary school mathematics; instead, it’s addition in a finite field. This means the addition results are taken modulo 256.

\(a \oplus b = (a + b) \mod 256\)

It is good to know that finite-fields have interesting properties:

- \((a \oplus b) \oplus c = a \oplus (b \oplus c)\)

- For every non-zero number \(x \in \mathbb{F}\), there is a number \(y\), where \(x \oplus y = 0\). \(y\) is known as the negative of \(x\).

In a finite field, the negative of a number can be calculated by subtracting that number from the field size (in this case, the size of our field is \(2^8=256\)). For example, the negative of \(10\) is \(256-10=246\), so \(10 \oplus 246 = 0\).

Surprisingly, the number \(246\), behaves exactly like \(-10\). Try adding \(246\) to \(15\). You will get \(246 \oplus 15 = 5\) which is the same as \(15 + (-10)\)! This has an important implication: we can perform subtraction without designing a new circuit! All we need to do is negate the number. Calculating the negative of a number is like taking the XOR of that number (Which gives \(255 - a\)), and then adding \(1\) to it (Which results in \(256 - a\), our definition of negation). This is known as the two's complement form of a number.

It’s incredible to see that we can build electronic machines capable of adding and subtracting numbers by simply connecting a bunch of transistors together! The good news is that we can go even further and design circuits that can perform multiplication and division, using the same approach we used for designing addition circuits. The details of multiplication and division circuits are beyond the scope of this book, but you are strongly encouraged to study them on your own!

Not gates can be fun too!

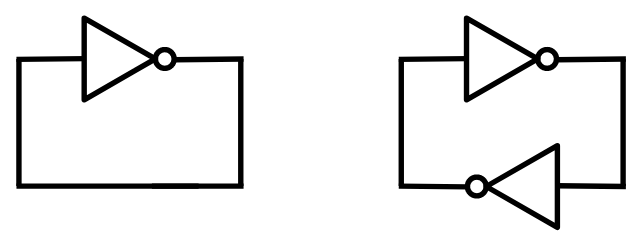

If you remember, we discussed that you can't build interesting structures using only a single type of single-input/single-output component (such as NOT gates). In fact, we argued that using just them, we can only create domino-like structures, where a single cause traverses through the components until reaching the last one. However, that's not entirely true: what if we connect the last component of the chain to the first one? This creates a loop, which is definitely something new. Assuming two consecutive NOT gates cancel each other out, we can build two different kinds of NOT loops:

After analyzing both possible loops, you will soon understand that the one with a single NOT gate is unstable. The voltage of the wire can be neither 0 nor 1. It creates a logical paradox, similar to the statement: This sentence is not true. The statement can be neither true nor false!

Practically, if you build such a circuit, it may oscillate rapidly between possible states, or the wire's voltage may settle at a value between the logical voltages of 0 and 1.

On the other hand, the loop with two NOT gates can achieve stability. The resulting circuit has two possible states: either the first wire is 1 and the second wire is 0, or the first wire is 0 and the second wire is 1. It will not switch between these states automatically. If you build such a circuit using real components, the initial state will be somewhat random. A slight difference in the transistor conditions may cause the circuit to settle into one of the states and remain there.

Try to remember

So far, we have been experimenting with stateless circuits—circuits that do not need to store or remember anything to function. However, circuits without memory are severely limited in their capabilities. To unlock their full potential, we need to explore how to store data within a digital circuit and maintain it over time. This is one of the most critical steps before we can build a computer, as computers are essentially machines that manipulate values stored in some kind of memory. Without memory, a computer cannot perform complex tasks or execute meaningful programs.

As a child, you may have tried to leave a light switch in a "middle" position. If the switch was well-made, you probably found it frustratingly difficult to do! The concept of memory arises when a system with multiple possible states can only stabilize in a single state at a time. Once it becomes stable, it can only change through an external force. In this sense, a light switch can function as a single-bit memory cell.

Another silly example: imagine a piece of paper—it remains stable in its current state. If you set it on fire, it gradually changes until it is completely burned, after which it stabilizes again. Keeping the paper in a "half-burned" state is not easy! You could consider the paper as a crude single-bit memory cell, but it has a major flaw: once burned, it cannot return to its original state.

Fortunately, there are ways to build circuits with multiple possible states, where only one state remains stable at a time. The simplest example is a circuit that forms a loop by connecting two NOT gates to each other. This setup involves two wires: if the first wire is 1, the second wire will be 0, and the circuit will stabilize in that configuration (and vice versa).

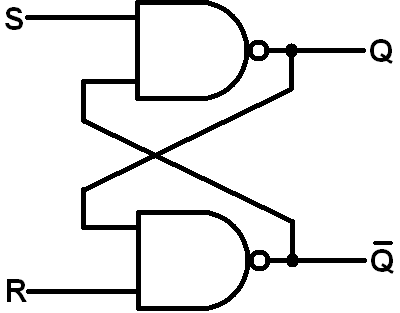

The problem with a simple NOT gate loop is that it cannot be controlled externally—it lacks an input mechanism to change its state. To fix this, we can replace the NOT gates with logic gates that accept two inputs instead of one. For example, using NAND gates instead allows us to introduce external control. By providing voltages to the extra input pins, a user can modify the internal state of the loop. This type of circuit is known as an SR latch:

Now, the user can set the latch to the first or second state by setting S=1 and R=0, or S=0 and R=1, respectively. The magic lies in the fact that the circuit will stably remain in the latest state, even after both S and R inputs are set to zero!

Here you can find an example of a SR latch implemented in Python:

def SRLatch(circuit, in_r, in_s, out_data, initial=0):

neg_out = circuit.new_wire()

Nor(circuit, in_r, neg_out, out_data)

Nor(circuit, in_s, out_data, neg_out)

neg_out.assume(1 - initial)

out_data.assume(initial)

Notice how we ingeniously feed two set/reset inputs into something that is essentially a NOT loop! Now, there’s something tricky about simulating a NOR/NOT loop: How can the first NOR gate function when neg_out is still not calculated? Or similarly, how can the second NOR gate calculate neg_out when out_data is still not calculated? There are two approaches we can use to resolve the chicken-and-egg problem in our simulation:

- Give up and attempt to simulate a memory-cell component without performing low-level transistor simulations. This would require us to define a new Primitive Component (similar to N/P transistors), which includes an

update()function that mimics the expected behavior of a latch. - Hint the simulator with the initial values of wires, and let the simulator to settle in an stable state by running the update function of the transistors for a few iterations and stopping the iterations after the wire values stop changing (Meaning that the system has entered a stable state).

That’s where the assume function we defined for our Wire class comes in handy. The assume function essentially hints to the simulator the initial value(s) of the wires in our memory cell, making it stable. In fact, if you don’t call these assume functions when defining the gates, the simulator won’t be able to simulate it, and the output of both NOR gates would become X. Assumption is only necessary when we want to initialize the circuit in a stable state for the first time. After that, the circuit will ignore the initial assumed values and will start working as expected. Note: In the real world, the memory cell randomly settles into one of the set/reset states due to environmental noise and slight differences between the transistors.

A more user-friendly latch

SR latches are perfect examples of memory cells since they can store a single bit of data. However, the unusual aspect of SR latches is that they require two inputs to determine whether to set them to a set (1) or reset (0) state. To set the latch to a 1 (set) state, you would feed it S=1 & R=0, and to reset it to 0 (reset) state, you would feed it S=0 & R=1. But what if we only had a single wire, D=0/1, and wanted the latch to remember the value stored in that wire? This is where the D-latch, a second type of latch, comes in handy.

Building a D-latch is quite straightforward: you simply need to create a circuit that decodes a single D bit into two S and R bits. The circuit should output SR=01 when D=0 and SR=10 when D=1. This circuit is essentially a 1x2 decoder, which can then be connected to your existing SR-latch.

There’s a problem when we simply connect a 2x1 decoder to an SR latch: how can we tell the latch to stop copying whatever value is present on the D wire into its internal state? In an SR latch, the answer is straightforward: when both S and R are set to 0, the latch’s internal state won’t change and will simply remain in its most recent state. We would like to have the same kind of control in a D-latch, or else the D-latch would be no different than a simple wire! To achieve this, we introduce a new control wire called clock (or clk), which stops the latch from acquiring the value of D. The truth table for such a circuit would look something like this:

| Previous state | CLK | D | Next state |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

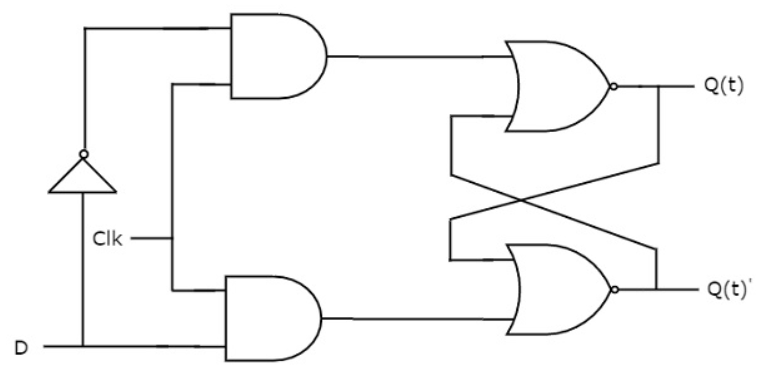

Here is how the schematic representation of a D-latch would look:

And how it can be represented with our Python simulator:

def DLatch(circuit, in_clk, in_data, out_data, initial=0):

not_data = circuit.new_wire()

Not(circuit, in_data, not_data)

and_d_clk = circuit.new_wire()

And(circuit, in_data, in_clk, and_d_clk)

and_notd_clk = circuit.new_wire()

And(circuit, not_data, in_clk, and_notd_clk)

neg_out = circuit.new_wire()

Nor(circuit, and_notd_clk, neg_out, out_data)

Nor(circuit, and_d_clk, out_data, neg_out)

neg_out.assume(1 - initial)

out_data.assume(initial)

Later in this book, we will be building a computer with memory cells of size 8 bits (a.k.a. a byte). It might make sense to group 8 of these DLatches together as a separate component in order to build our memory cells, registers, and RAM. We'll need to arrange the latches in a row and connect their enable pins together. The resulting component will have 9 input wires (1-bit in_clk and 8-bit in_data) and 8 output wires (8-bit out_data):

class Reg8:

def snapshot(self):

return wires_to_num(self.out_data)

def __init__(self, circuit, in_clk, in_data, out_data, initial=0):

self.out_data = out_data

for i in range(8):

DLatch( # WARN: A DLatch may not be appropriate here...

circuit,

in_clk,

in_data[i],

out_data[i],

ZERO if initial % 2 == 0 else ONE,

)

initial //= 2

There is something wrong with this register component. Let's discover the problem in action!

Make it count!

Since we now know how to build memory cells, we can create circuits that maintain state/memory and behave accordingly! Let's build something useful with it!

A very simple yet useful stateful circuit you can build, using adders and memory cells, is a counter. An 8-bit counter can be made by taking the output of an 8-bit memory cell, incrementing it, and then feeding it back to the input of the memory cell. In this case, we expect the value of the counter to be incremented every time the clock signal rises and falls. Here’s what the Python simulator for an 8-bit counter would look like. Try running it, and you’ll see that the simulator gets stuck and is unable to stabilize!

class Counter:

def snapshot(self):

print("Value:", self.counter.snapshot())

def __init__(self, circuit: Circuit, in_clk: Wire):

one = [circuit.one()] + [circuit.zero()] * 7

counter_val = [circuit.new_wire() for _ in range(8)]

next_counter_val = [circuit.new_wire() for _ in range(8)]

Adder8(

circuit,

counter_val,

one,

circuit.zero(),

next_counter_val,

circuit.new_wire(),

)

self.counter = Reg8(circuit, in_clk, next_counter_val, counter_val, 0)

if __name__ == "__main__":

circ = Circuit()

clk = circ.new_wire()

OSCILLATOR = "OSCILLATOR"

clk.put(OSCILLATOR, ZERO)

counter = Counter(circ, clk)

print("Num components:", circ.num_components())

while True:

circ.stabilize() # WARN: Gets stuck here!

counter.snapshot()

clk.put(OSCILLATOR, 1 - clk.get())

When you think about it, the reason the circuit doesn’t stabilize becomes clear: as soon as the clock signal rises to 1, the feedback loop activates and continues to operate as long as the clock remains at 1. However, the clock signal stays at 1 for a certain period before dropping back down to 0. During that time, the circuit keeps trying to increment the value of the memory cell, which prevents it from stabilizing. We introduced the clock signal to allow us to control our stateful circuit as it iterates through different states, but it seems that a DLatch isn't giving us the control we need.

In fact, the enable input of the D-Latch (the clock signal) should be set to 1 for only a very short time—we just need a brief tick. Otherwise, the circuit will enter an unstable state. As soon as the input of the memory cell is captured, the output will change shortly after. If the enable signal is still 1, the circuit will continue incrementing and updating its internal state. The duration for which the enable signal is 1 should be short enough that the incrementor component doesn't have enough time to update its output, Otherwise, our circuit will be no different from connecting the output of a NOT gate to its input, in terms of instability!

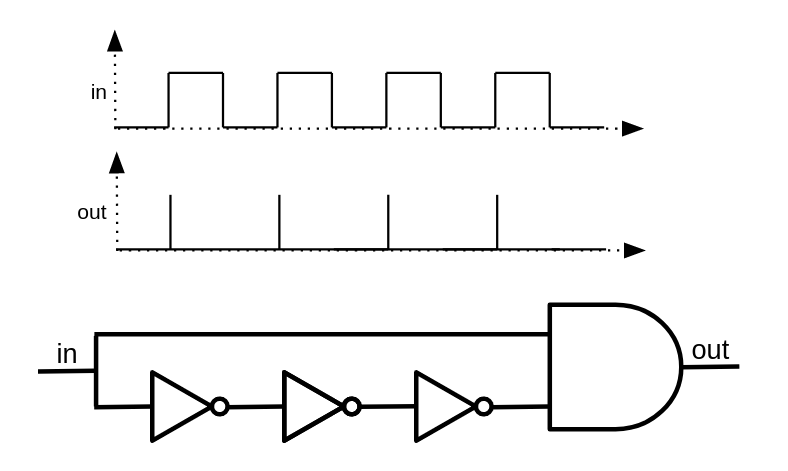

A straightforward idea for solving the problem is to make the time the clock stays high short enough to resemble a pulse—just long enough to let the circuit transition to its next state, but not so long that it starts looping and becomes unstable. One way to create such pulses is by passing a typical clock signal through an edge detector. An edge detector is an electronic circuit that can recognize sharp changes in a signal.

So, how can we build an edge detector? There's an interesting twist in the real world that we can exploit: because logic gates have propagation delays, unusual behaviors—known as hazards—can occur. These are brief, unintended outputs caused by timing mismatches in signal changes.

Consider this example circuit:

When the input is 0, the NOT gate outputs 1. Now, when the input switches to 1, the wire that goes directly to the AND gate receives 1 immediately. However, the wire that goes through the NOT gate takes a brief moment to reflect the change, still holding 1 for a short time before it becomes 0. During that brief moment, both inputs of the AND gate are 1, causing it to produce a short, unintended high output—a glitch or pulse.

By closely observing the behavior of this circuit, we can see that it effectively converts a clock signal into a train of ultra-short pulses. If we connect this component to the enable pin of a latch, the latch will update only on the rising edge of the clock signal. This configuration is known as a flip-flop.

The only difference between a flip-flop and a latch is in how they respond to the clock: flip-flops are edge-triggered, while latches are level-triggered. Flip-flops are preferred when designing synchronous circuits, as they provide better timing control and predictability.

Unfortunately, our digital circuit simulator is not a perfect representation of the real world. Since it doesn't account for gate delays, we can't build edge detectors as we discussed earlier. Even if we could, it wouldn't be a very clean solution for someone like me, who tends to be a bit paranoid. Just imagine if one of those pulses happens to be shorter or longer than expected—it could break the entire computation!

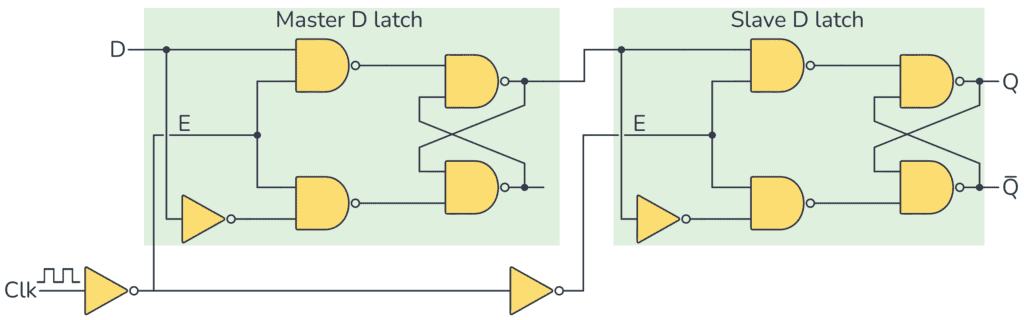

Fortunately, there's a cleaner and more reliable way to solve the looping problem, one that doesn’t rely on exploiting subtle physical behaviors. It starts by breaking the loop through serially connecting two D-latches: one that activates when the clock signal goes low, and the other when the clock signal goes high. This way, there is no point in time when both latches are active, so a loop can't form, even though data is still being reliably stored. Curious why it's called a flip-flop? When the clock signal rises, the first D-latch gets activated and it "flips." Then, when the clock signal falls, the first latch becomes inactive, the second latch activates, and it "flops!" And just like that, we form a flip-flop!

Here's the Python implementation of the structure we just described:

def DFlipFlop(circuit, in_clk, in_data, out_data, initial=0):

neg_clk = circuit.new_wire()

Not(circuit, in_clk, neg_clk)

inter = circuit.new_wire()

DLatch(circuit, in_clk, in_data, inter, initial)

DLatch(circuit, neg_clk, inter, out_data, initial)

In our Counter circuit example, substitute the registers we built with DLatches with ones built using DFlipFlops, and the stabilization problem is solved!

Counters on steroids!

A counter circuit is a perfect example of how digital circuits can remember their state and transition to a new state in a controlled fashion. It’s also a fundamental concept that inspires us to build much more complex systems, including computers.

A computer, in its simplest form, consists of memory, which stores all instructions and data, and a CPU, which fetches and interprets them. Looking closely at the whole system, you can see that the CPU/memory pair is not very different from the register/incrementer pair in a counter circuit. There is a state (in the counter circuit, a single byte within a register; in the computer, several billion memory cells), and there is a state manipulator (in the counter circuit, an incrementer; in the computer, a component that decodes the current instruction and executes it). On every clock pulse, the old state is processed by the manipulator, and the result is saved back into the state holder.

However, there is an important difference: in the case of a computer, we can't feed the entire state (all several billion 8-bit cells) into the manipulator to compute the next state—that would be enormous. It would require a giant manipulator circuit and billions of wires, which is excessive for a state change that typically affects only a small portion of the entire state.

We don't want to give up on having a large memory. But as previously mentioned, a single state transition typically affects only a small portion of the overall state. So, we don’t need to feed the entire memory into the manipulator—we only need to feed in the parts that are relevant.

But how do we specify which part of the memory we want to use?

A smarter state storage

The solution is simple but powerful: let's assign a unique identity to each memory cell and call it its address. That way, we can reference and access only the specific parts of memory we need during each operation.

Yes, what we need is an Addressable Memory.

In this section, we're going to implement a very simple—and admittedly foolish—way to build an addressable memory. I say "foolish" because the memory in a typical computer is far more complex and efficient than what we're about to construct. But that's fine—the goal here isn't efficiency. It's to understand the core concept and to get creative with the tools we already have.

So, let’s begin by defining what we want to build. We'll assume we're designing an 8-bit computer. This computer will have a CPU capable of handling 8-bit instructions and an addressable memory (RAM) with an 8-bit address space. That means it will contain \(2^8 = 256\) memory cells, and each cell will store 8 bits of data. A 256-byte random-access memory, which is embarrassingly small by today's standards!

In this section, we’ll focus specifically on building the RAM component.

Given these specifications, our RAM will need:

- 8 address input wires — to specify the memory cell we want to read from or write to.

- 1 read/write control wire — to determine whether the operation is a read or a write.

- 8 data input wires — used only in write mode, to supply the value to store at the specified address.

- 8 data output wires — used only in read mode, to output the value stored at the specified address.

That gives us a total of 17 input wires (8 for address, 8 for data-in, 1 for read/write control) and 8 output wires (for data-out).

Now the challenging question is how to allow only a single 8-bit memory-cell to be read/written, given an address? Not too hard, let's solve the problem for read and write operations independently.

Selective writing

Let's assume that the 8-bit input pins of all the memory cells within our memory are connected to the 8 input pins of the memory component. This would cause the internal value of every memory cell to be updated to the given input value on the next clock cycle. We definitely don't want that! So how can we prevent it?

Remember how a register only stores its input value when a full clock cycle occurs? We can use a similar idea here. Specifically, we need to prevent the clock signal from reaching all memory cells except the one whose address matches the input address. Additionally, when the memory is in read mode, the clock signal should be completely disabled for all memory cells.

Technically, the clock signal should only reach a memory cell if: (addr == cell_index) && write_mode. To achieve this, simply set the input clock signal of each memory cell to: (addr == cell_index) && write_mode && clk

If you're still unsure why this works, try analyzing the value of the equation for different input scenarios.

If write_mode is false, the entire expression evaluates to false for all memory cells, which is exactly what we want—no writes occur. If the address provided to the memory component doesn't match a given cell's index, the expression again evaluates to false, regardless of whether write_mode is true or whether the clock signal is high. This, too, is the intended behavior.

However, when the memory is in write mode and the address matches a specific memory cell’s index, the condition becomes: true && true && clk = clk

This means the global clock signal is effectively passed through to only that memory cell, allowing it to store the input value on the next rising edge—just as intended.

Implementation-wise, we already have AND gates, and the only missing piece is the ability to check the equality of two 8-bit values. As always, it's best to start simple: we'll first design a circuit that can check the equality of two single bits, and then extend that solution to handle multi-bit inputs.

To achieve this, we'll create two modules:

Equals: This module checks the equality of two single bits. Functionally, it's justNot(Xor(a, b)).MultiEquals: This module checks the equality of two multi-bit values. It will be especially useful for comparing memory addresses and decoding instructions in the sections to come.

def Equals(circuit, in_a, in_b, out_eq):

xor_out = circuit.new_wire()

Xor(circuit, in_a, in_b, xor_out)

Not(circuit, xor_out, out_eq)

def MultiEquals(circuit, in_a, in_b, out_eq):

if len(in_a) != len(in_b):

raise Exception("Expected equal num of wires!")

count = len(in_a)

xor_outs = []

for i in range(count):

xor_out = circuit.new_wire()

Xor(circuit, in_a[i], in_b[i], xor_out)

xor_outs.append(xor_out)

inter = circuit.new_wire()

Or(circuit, xor_outs[0], xor_outs[1], inter)

for i in range(2, count):

next_inter = circuit.new_wire()

Or(circuit, inter, xor_outs[i], next_inter)

inter = next_inter

Not(circuit, inter, out_eq)

To keep our implementation of MultiEquals efficient—especially since we'll use many of them in our RAM module—we'll avoid the naive approach of using an array of Equals components followed by a big AND gate.

Instead, we'll take a more optimized route:

- XOR each pair of corresponding bits from the two inputs. This will produce a 1 for any position where the bits differ.

- OR all the XOR results together. If any pair of bits is unequal, the result will be 1.

- NOT the final result. This gives us 1 only if all bits are equal—exactly what we want.

This approach reduces the depth of the logic and avoids constructing redundant gates, making it both faster and more resource-efficient.

Selective reading

The read-mode scenario is even simpler. Memory cells continuously output their internal values to their output pins, regardless of the clock signal—so the clock doesn't matter at all in this case. What we do need is a way to select which register's outputs should be routed to the memory component’s output pins, based on the given address.

To handle this, we introduce a new and very useful component: the multiplexer. Before moving on to our final RAM implementation, let’s take a closer look at how a multiplexer works and how it can be implemented.

A vanilla multiplexer is a digital circuit that takes in \(2^n\) input bits—representing the options to choose from—and another \(n\) bits as a selection input, which tells the circuit which option to access. The output is a single bit: the value of the selected input at the specified index.

You can think of a multiplexer as being conceptually similar to accessing a boolean array: output = data[selection], where data is a bit array with \(2^n\) elements and selection is an \(n\)-bit value indicating which array entry to output.

You can start by building a 2-input multiplexer and then use it to construct larger multiplexers. A 2-input multiplexer takes two data bits as available options and a single selection bit. If the selection bit is 0, the first data bit is output. If the selection bit is 1, the second data bit is output.

Here is a truth-table for the multiplexer described:

| data | sel | out |

|---|---|---|

| 00 | 0 | 0 |

| 00 | 1 | 0 |

| 01 | 0 | 0 |

| 01 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 |

| 11 | 0 | 1 |

| 11 | 1 | 1 |

Which can be easily constructed using basic logic gates:

out = (!data[0] & sel) | (data[1] & sel)

And here is the equivalent Python component:

def Mux1x2(circuit, in_sel, in_options, out):

wire_select_not = circuit.new_wire()

and1_out = circuit.new_wire()

and2_out = circuit.new_wire()

Not(circuit, in_sel[0], wire_select_not)

And(circuit, wire_select_not, in_options[0], and1_out)

And(circuit, in_sel[0], in_options[1], and2_out)

Or(circuit, and1_out, and2_out, out)

Now given two \(2^n\) input multiplexers you can build a \(2^{n+1}\) multiplexer!

- A \(2^{n+1}\) input multiplexer has \(2^{n+1}=2 \times 2^n\) inputs.

- Feed the first \(2^n\) input bits to the first multiplexer and the second \(2^n\) input bits to the second multiplexer.

- Connect the first \(n\) bits of the \(n+1\) selection pins to both multiplexers.

- Now you have two outputs—one from each multiplexer. The final output depends on the last (most significant) selection bit. Use a 2-input multiplexer to select between these two outputs and compute the final result.

We can define a meta-function that generates multiplexer component creators, given the number of input pins and a multiplexer component with one fewer selection bit.

For example, you can build a \(2^5\)-input multiplexer using two \(2^4\)-input multiplexers like this: Mux5x32 = Mux(5, Mux4x16)

Then, we’ll iteratively build a \(2^8=256\) input multiplexer, which is exactly what we need for constructing our 8-bit RAM:

def Mux(bits, sub_mux):

def f(circuit, in_sel, in_options, out):

out_mux1 = circuit.new_wire()

out_mux2 = circuit.new_wire()

sub_mux(

circuit,

in_options[0 : bits - 1],

in_options[0 : 2 ** (bits - 1)],

out_mux1,

)

sub_mux(

circuit,

in_sel[0 : bits - 1],

in_options[2 ** (bits - 1) : 2**bits],

out_mux2,

)

Mux1x2(circuit, [in_sel[bits - 1]], [out_mux1, out_mux2], out)

return f

Mux2x4 = Mux(2, Mux1x2)

Mux3x8 = Mux(3, Mux2x4)

Mux4x16 = Mux(4, Mux3x8)

Mux5x32 = Mux(5, Mux4x16)

Mux6x64 = Mux(6, Mux5x32)

Mux7x128 = Mux(7, Mux6x64)

Mux8x256 = Mux(8, Mux7x128)

Now we're fully ready to move forward and implement our RAM design!

Chaotic access

First things first—what do we mean by random-access memory?

Because in RAM, it's very efficient to read or write a value at any address, regardless of its position. The key idea is that accessing a memory cell takes the same amount of time no matter which address is used.

Now, compare this to how optical disks or hard drives work. These devices have to keep track of the current read/write head position, and to reach a new location, they must seek—move to the requested position relative to where they are. This makes access efficient only when reading or writing data sequentially, like going forward or backward one byte at a time.

However, real-world programs don't access memory so predictably. Instead, they often jump around, requesting data from widely different memory addresses. Since these access patterns are hard to predict, we call it "random access." And RAM is designed specifically to handle such patterns efficiently.

As discussed in the previous section, the read and write modes of our RAM work independently. For the write-mode functionality, we simply need to initialize 256 8-bit registers using a loop and condition their clock signals.

While tracking their outputs in the wire array reg_outs, we’ll use eight Mux8x256 components to select which register's output pins should be routed to the RAM’s output. Eight multiplexers are required because each of our registers has 8 bits.

class RAM:

def snapshot(self):

return [self.regs[i].snapshot() for i in range(256)]

def __init__(self, circuit, in_clk, in_wr, in_addr, in_data, out_data, initial):

self.regs = []

reg_outs = [[circuit.new_wire() for _ in range(8)] for _ in range(256)]

for i in range(256):

is_sel = circuit.new_wire()

MultiEquals(circuit, in_addr, num_to_wires(circuit, i), is_sel)

is_wr = circuit.new_wire()

And(circuit, is_sel, in_wr, is_wr)

is_wr_and_clk = circuit.new_wire()

And(circuit, is_wr, in_clk, is_wr_and_clk)

self.regs.append(

Reg8(circuit, is_wr_and_clk, in_data, reg_outs[i], initial[i])

)

for i in range(8):

Mux8x256(

circuit, in_addr, [reg_outs[j][i] for j in range(256)], out_data[i]

)

Soon, you’ll realize that our simulator isn't efficient enough to handle transistor-level simulations of RAM, especially as memory size grows. To keep things practical, it makes sense to cheat a little and provide a secondary, faster implementation of RAM—a primitive component described directly in plain Python code, much like how we handled transistors.

class FastRAM:

def snapshot(self):

return self.data

def __init__(self, circuit, in_clk, in_wr, in_addr, in_data, out_data, initial):

self.in_clk = in_clk

self.in_wr = in_wr

self.in_addr = in_addr

self.in_data = in_data

self.out_data = out_data

self.data = initial

self.clk_is_up = False

circuit.add_component(self)

def update(self):

clk = self.in_clk.get()

addr = wires_to_num(self.in_addr)

data = wires_to_num(self.in_data)

if clk == ZERO and self.clk_is_up:

wr = self.in_wr.get()

if wr == ONE:

self.data[addr] = data

self.clk_is_up = False

elif clk == ONE:

self.clk_is_up = True

value = self.data[addr]

for i in range(8):

self.out_data[i].put(self, ONE if (value >> i) & 1 else ZERO)

return False

Alright folks—the "state" storage part of our magical CPU/memory duo is now up and running! Now it’s time to build the state manipulator—the CPU itself—and bring everything together to finalize our design of a computer!

The manipulator

Our definition of a computer in this chapter is a machine that can be programmed—something on which you can deploy arbitrary algorithms. We want this program to be replaceable, meaning we may deploy one program now and later substitute it with another. Therefore, it makes perfect sense that the programs on this computer need to be stored in some form of alterable memory.

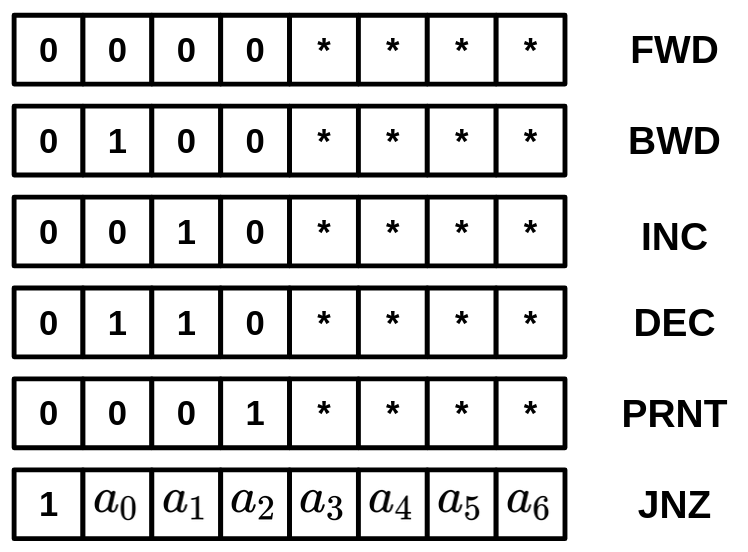

Our construction of memory is simply an addressable group of memory cells that can store a certain number of bits. So, the "programs" we're referring to must be representable in a binary format—otherwise, how could they persist in memory that only stores data as bits?

In this section, we will discuss how we can assign meaning to numbers and bit patterns. Essentially, we want to design a very simplistic mapping from 8-bit values to "meanings." These mappings will make up the instruction set of our computer. We'll also design circuits that can fetch those values from memory, interpret them, and execute their intended operations.

Before diving into this book's design and implementation of a processor, there’s an important question we need to address. Computer programs need a place to store and manipulate temporary values—much like using a sheet of paper as a draft when solving a math problem. That’s actually one of the primary reasons computers have memory. But we just said that a "program" itself is also data stored in memory. So, is the memory used by the program for drafting its data the same as the memory where the program itself is stored? Or are these two separate memory spaces?

For modern computers, the answer is yes—both the program and its data reside in the same memory. This concept is often summed up by the phrase: code is data, and data is code. It's one of the most brilliant and fundamental ideas that form the basis of modern computing.

The implications of this design—known as the Von Neumann architecture—are profound. When a computer stores both the program and the data it operates on in the same memory, several important things become possible: